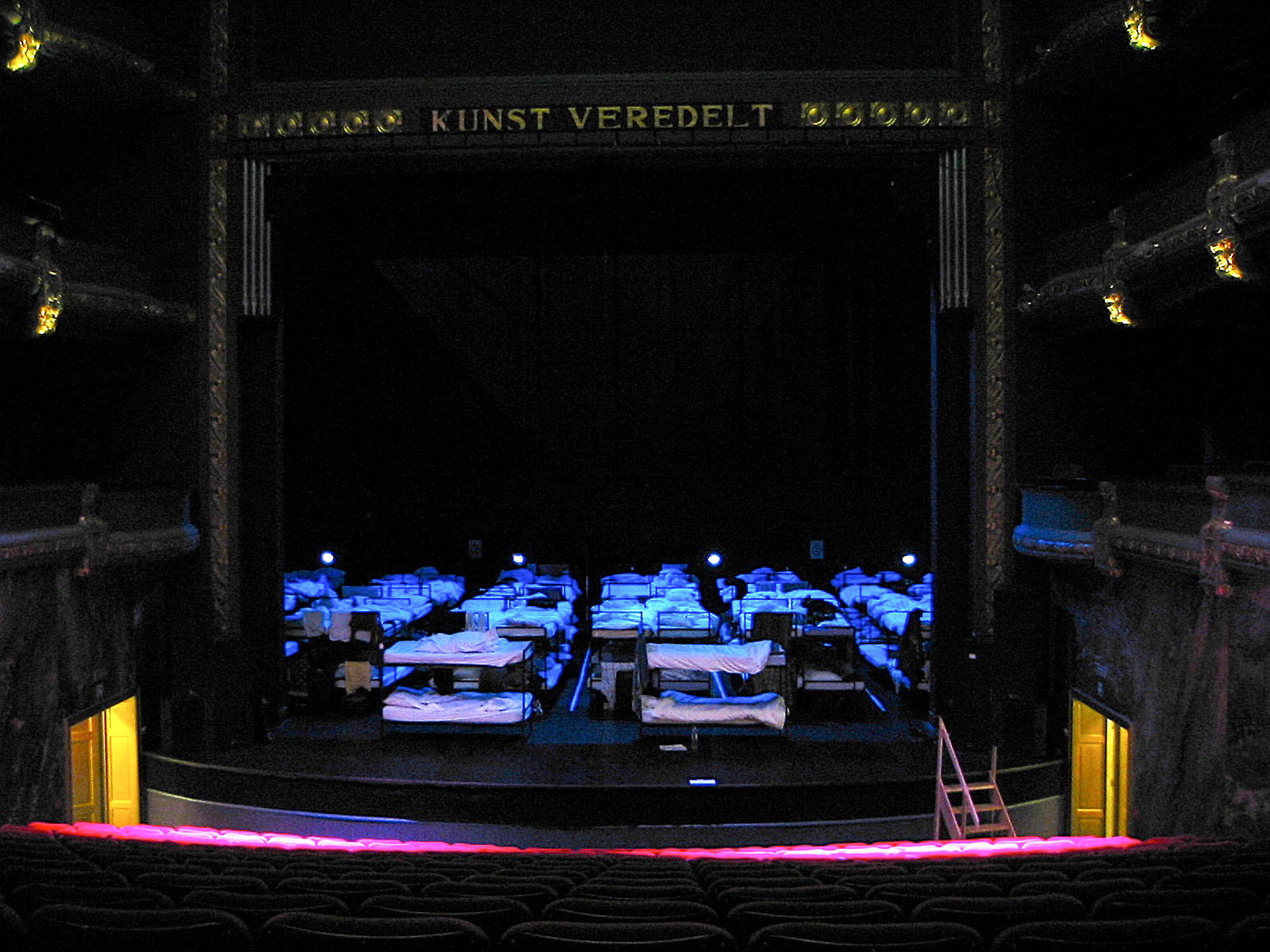

deufert&plischke, B-Visible, Kunstencentrum Vooruit 2002.

Photography: Florian Malzacher

Photography: Florian Malzacher

Empty Stages, Crowded Flats

Performative curating performing arts

By Florian Malzacher

Let’s start with an image: Two, three lonely people scattered around midnight

The German choreographers Kattrin Deufert and Thomas Plischke put this unlikely, modest spectacle in the centre of their curatorial project B-Visible, a programme consisting of performances, lectures, and other interventions loosely dispersed over the course of 72 hours. These take place everywhere in the theatre – except at its heart, the main stage, the default centre of attention. Here it is completely silent, a refuge for anyone who wants to take a break.1

B-Visible laid out what it could mean to understand curating in performing arts differently than just programming a couple of shows within a season. How even classic theatre spaces can be challenged when approached and confronted in their site specificity – and within the conventions of time. By using their limitation as productive frictions (with regards to the architecture: by reversing its logic) and at the same moment taking them radically serious (in terms of time: After all, theatre buildings are constructed to keep the daily life away, so why not ignoring the real time of the outside world completely).

deufert&plischke played with this very core element of theatre – creating an experience for a temporary community in relation to time and space – by using them as their main means for curating. There is much more to gain than most festival or season programs try to satisfy us with.

“Diaghilev, the most important curator of the 20th century”

Whether the term curating – obviously borrowed from visual arts – is the best choice in the context of live arts can be discussed. But within the specific field of performing arts I am referring to (a theatre that refuses to be defined by the borders of drama, of conventional divisions between performance and audience, of the imposed limitations of the genre. A theatre that finds itself mostly outside of the fixed structures and relatively fixed aesthetics of the repertory city theatres, which are mostly active only within the limits of their own countries and languages). Terms, concepts and definitions are a problematic issue in any case: Already the question of how to name the genre (performing arts, experimental theatre, post-dramatic theatre, devised theatre, live arts, conceptual dance etc. etc.) is a subject of great confusion. Why I do believe in promoting the concept of curating on this highly contested aesthetical playground lies precisely in the expectations it raises: Expectations that pose a clear challenge to everyone calling him/herself a curator. This distinction is not for the purpose of hipness or prestige, but with the aim of signifying a shift in understanding the possibilities and claims of programming arts as well as understanding it as a performative task itself.

The fact that the figure of the exhibition maker – primarily and almost synonymous with the new type of curator: Harald Szeemann – became so important in the 1970s is due not least to the fact that the concept of the nature of an exhibition radically had begun to change. Following the increased interest in performativity within visual arts since the 1960s (in form of performance, installation, happening etc.), exhibitions became more alive, and accompanied events which sometimes changed after the opening… New forms of time and spatial experiences were developed. Art shows created their own dramaturgies. Szeemann compared his work quite early with that of a theatre director. Beatrice von Bismarck recently underlined the proximity of exhibition making to the job of a dramaturge, and Maria Lind speaks of her practice as “performative curating”. Since the 1990s, art continued to force these traditions by expanding the exhibition framework and discovering itself as a social space.2 It is hardly possible to penetrate more deeply into the neglected core business of the theatre.

Using the concept of “curating” within performing arts only makes sense when meant to emphasise the possibilities of an expanded definition of what theatre is and can be. And if programming itself is understood as part of the medium theatre. In fact, one of the key figures of contemporary curating in visual art, Hans Ulrich Obrist, stated that “the most important curator of the 20th century” is someone from the field of performing arts: Sergei Diaghilev, the famous impresario of the Ballets Russes. “He brought together art, choreography, music… Stravinsky, Picasso, Braque, Natalia Goncharova… the greatest artists, composers, dancers and choreographers of his time.”3

“Programme making” (like exhibition making before the curatorial turn in visual arts) generally understands each work of art, each performance as an independent artistic expression that is supposed to live on its own. The programmer primarily provides the stage for the artist’s endeavour, enables it, tries to offer best conditions, communicates it to the audience etc. Recently these loyalties have often – for obvious reasons – been contested and have shifted towards a loyalty rather to the own institution – festival or venue – which is threatened by lack of subsidies or political attacks. Saving the institution is now often seen as the ultima ratio.

Curating performing arts for me would not mean to ignore these points. The artistic work itself obviously has to stay in the centre, and saving the institution one is responsible for is obviously also not a bad idea. But to shift the weights in order to make room for another aspect: The necessity of putting works into a larger context, to make them interact with each other and the world around, rather than seeing them as entities. Also, to offer a collective experience not only during or within the performance itself, but through turning the festival, the event, or the venue into a larger field of performative communication.

Keeping and loosing control

To understand the specific situation of the international independent theatre scene it is crucial to understand that it is a quite young phenomenon, which primarily began in the 1980s. This was a period when radically new aestheticisms, and subsequently new working structures and hierarchies within ensembles, collectives, and companies came into existence along with new or newly defined theatre houses such as Mickery in Amsterdam, Kaaitheater in Brussels, de Single in Antwerp, Hebbel-Theater in Berlin, TAT (Theater am Turm) in Frankfurt, Teatergarasjen in Bergen, Ménagerie de verre in Paris and many more. Additionally, festivals like Eurokaz in Zagreb, Inteatro in Polverigi, Festival d’Automne in Paris and later KunstenfestivalDesArts in Brussels, as well as the professional network IETM, offered new possibilities for a dense international exchange. Above all, the concept of the Belgium kunstencentra like Vooruit in Gent or Stuk in Leuven (which, with their open, often interdisciplinary approaches, replaced conventional ensemble theatres) has spilled over into neighbouring countries and made it possible to reinvent theatre as an institution.

With them arrived a new, often charismatically filled professional profile: that of the programme maker. As the name already shows, the accent was on “making”. A generation of men of action defined the course of events – and even if their attitude seems occasionally patriarchal from today’s point of view, the scene was actually less male-biased than the society and the city theatres around it. This generation of founders, which at the same time redefined and imported the model of the dramaturge, established some remarkably efficient and stabile structures and publics: it was a time of invention and discovery, which has had obvious repercussions into the present day. Professional profiles were created and changed – including that of the artist.

This foundation work was (at least in the west) largely completed by the mid-1990s and what followed was a generation of former assistants, of critical apprentices so to say, and with them a period of continuity, but also of differentiation, reflection, and well-tailored networks, of development and re-questioning new formats – labs and residencies, summer academies, parcours, thematic mini-festivals, emerging artist platforms…

The picture is still dominated by transition models, but the strong specialization of the arts (exemplified by the visual arts), the subsequent specialization of the programme makers and dramaturges, and a generally altered professional world – which also here increasingly relies on free, independent, as well as cheaper labour – along with increasingly differentiated audiences, again require a different professional profile. The curator is a symptom of these changes in art, as well as in society and the market. His working fields are theatre forms that often cannot be realized within the established structures; artistic handwritings that always require different approaches; a scene that is increasingly internationalized and disparate; the communication of complex aestheticisms; transmission and contextualization. Last but not least, the curator is the link between art and the public.4

While keeping in mind the possibilities curating performing arts can offer for the artistic work as well as for the audience, it is apparent that presenting works of live art is dominated to quite a degree by pragmatics. Performances are not paintings, easily transportable artefacts, or at least clearly defined installations. Few exhibitions have the complexity and unpredictability of a festival. As a social form of art, theatre will always have a different attitude towards pragmatism and compromise, will need more time and space, an therefore stay inferior to other genres regarding agility. In an age of speed and spacelessness that could represent a market flaw, just as it was an advantage in other times. But however small the possibilities of contextualisation may be within a festival or a season, they can also be very effective. The fact of not-being-able to control is a challenge that must be faced in a productive way.

Programming – as curating – is about selecting – a selection that might be contested, that in the end refers to specific discourses and also to taste and opinion. On one hand, there will always be the accusation of being too narrow (mainly coming from audiences, critiques, artists that don’t feel represented by those choices). On the other hand, many programmes of theatres and festivals are so wide that they seem arbitrary. The reasons for the choices made become even more vague, unclear, hidden, and imprecise. The arguments for keeping it somewhat broader are numerous, and all programme makers are educated in them. Some examples are creating contexts, not excluding any segment of the public, placing more audacious pieces aside next to more popular ones, visitor numbers, ticket sales, tolerance towards other artistic approaches, financial difficulties and more. Indeed, it doesn’t help anyone if a curator wants to primarily prove his own courage with his programme – eventually at the cost of the artists. To establish and maintain a festival or a venue, to bind an audience, to win allies, and thus to create a framework also for artworks that are more consequential, more audacious, and more cumbersome is important. Especially since free spaces for art are becoming fewer and fewer, since the struggle of all programme makers for the survival of their programmes is becoming tougher and tougher.

And yet, what is the use of maintaining that which should actually be maintained if it is no longer visible? If it is no longer legible, what is the necessary and compellable in the midst of the pragmatic? The model of the curator is also a counter-model of the cultural manager, who values many things, who stakes off a broad field of creativity and artistic activities, whose aim is, after all, socio-cultural. Curatorial work also means deciding clearly for oneself what is good and what is bad. And knowing why.

But a good programme does not consist simply or necessarily only of good performances. On the one hand, the decision in favour of co-productions and against merely shopped guest performances is immensely important in terms of cultural policy. But there is also a decision for risk, the results imponderable; the right decisions can lead to a bad festival if one reads it only with respect to its results rather than its endeavours. On the other hand, it is about creating internal relationships – even if a festival does not give itself a thematic red thread. Whether a programme is well thought out depends on the combination of different formats, aestheticisms and arguments within a nevertheless very clearly outlined profile. But it also depends on the supposedly more pragmatic, but often no less dramaturgical considerations, which can play a considerable role in the beauty of a programme: for it can indeed happen that a performance is simply too long for a particular slot. Or too short. Or needs a different sort of stage. That it is the wrong genre. Thematically or aesthetically too similar to another show. Or too different. And yet, if it is worth it, one will probably find a solution. And yes, one must also fill in the slots: young, entertaining, political, conceptual, new, established... But there is also this: as soon as one stumbles across a piece that one wants to present by all means, one will quickly forget about this basic structure.

The curatorial

Several related interest shifts in recent art discourse fall together: The increasing attention in visual arts for the performative, for choreography and theatre. The new focus on the curatorial in performing arts, emphasising the specific means of the medium. And what Claire Bishop influentially describes as a “social turn”: The growing attention of artists for collaborative practices, and for the participation of the public, that leads to an art “in which people constitute the central artistic medium and material, in the manner of theater and performance.”5

All these aspects come into play when we try to describe the curatorial in the performing arts: The “curatorial”, a term used by scholars like Irit Rogoff or Beatrice von Bismarck, is not identical with the job of curating. While “curating” is widely seen as a professional set of skills, techniques, activities and practices, used to create a product (like an event, a exhibition, a festival), the curatorial is considered by Beatrice von Bismarck as something wider into which the activities of curating feed: “Curating is a constellational activity. By combining things that haven’t been connected before – artworks, artefacts, information, people, sites, contexts, resources, etc. – it is not only aesthetically, but also socially, economically, institutionally, and discursively defined. I understand it less as representation driven than motivated by the need to become public.” Compared to this “the curatorial is the dynamic field where the constellational condition comes into being. It is constituted by the curating techniques that come together as well as by the participants – the actual people involved who potentially come from different backgrounds, have different agendas and draw on different experiences, knowledges, disciplines – and finally by the material and discursive framings, be they institutional, disciplinary, regional, racial, or gender specific.”6

Irit Rogoff additionally and in slight difference emphasises on the level of practice the question of “how to instantiate this as a process, how to actually not allow things to harden, and how to create a public platform that allows people to take part in these processes.”7

A “dynamic field”, “a process, how to actually not allow things to harden” – already these description make clear how much the concept of the curatorial is thought as performative. And how much the fear of something that might look too “complete”, too much like “a finished product” already is a constituting part of all live arts, where the permanent proximity to failure, chance, mistakes and – as already mentioned – loss of control and compromises are not seen as necessary flaws but rather as the core of the medium theatre: “What’s specific to the theater,” Heiner Müller used to say, “is not the presence of the living actor or of the living spectator, but rather the presence of the person who has the potential to die.”8

Many curatorial concepts in performing arts therefore push the risk of failure far to make it tangible for the audience and create a special tension of aliveness. Expanding time might be such a push (playing with strength, exhaustion, boredom, enthusiasm of the collective body of the visitors). A density or complexity of space might be another one. But also the confrontation of works that might not be compatible on first sight creates a tension and openness through their friction.

Theatre is the space where societies always has explored their own means, procedures, ideals and limits. Theatre is, as Hannah Arendt states, “the political art par excellence; only there is the political sphere transposed into art.”9

Making this productive also in the creation of a curatorial field leads to Chantal Mouffe’s concept of agonism, a political concept that aims at showing different positions in struggle and disagreement (in opposition as well to Marx’s conception of materialism which would end in a harmonic society). By using the concept of agonistic pluralism Mouffe enables us to think democracy differently: Not as a necessary or even possible consensus but rather to always allow the possibility that conflict appears. Democracy is the arena where we can enact these differences. Just as the concept of the curatorial is thought as performative, the concept of agonism almost seems like paraphrasing theatre. Not by chance it draws its name from agon, the game, the competition. We need playful (while often very serious) agonism to prevent an antagonism that ends all positive negotiation. Without neglecting the obvious problems in transferring a concept of political theory into the realm of aesthetics: The idea of a curatorial, performative field that keeps things in flux and enables a playful (but serious) enacting of different positions is the, perhaps slightly utopian, vision of what curating in performing arts should aim for.

Challenging Spaces

Theatre still is mostly bound to certain spaces reserved exclusively for its practice: proscenium stages and black boxes. But even in the most conventional settings an awareness of the specificity of the space can produce artistic or curatorial added value: How does the audience enter the space? When does the performance actually begin? At the entrance door of the theatre? In the foyer? In the auditorium? What difference does it make when I have to enter from a different way than usually? Is it part of the performance or mere pragmatics? What are the rules of the theatrical contract in this case?

Even conventional theatre spaces are not neutral.

On one hand they provide necessary technical equipment, protect the work from unwanted encounters with the environment around, enable concentration, protect the artistic clarity etc. On the other hand these spaces themselves define largely already the possible outcome. Not only are they limited in terms of architecture, possible spatial arrangements. They also represent a certain idea of institution as it was mainly formed in the late 18th, early 19th century. Their inherent structures not only reproduce certain conventions of what theatre is supposed to be but also a certain image of society. They frame and often tame artistic as well as political visions. It is therefore no surprise that many curatorial projects in the field of theatre either leave these predetermined spaces or try to challenge them (as deufert&plischke did with B-Visible).

The hype around site specific works mainly from the mid-90s onwards put a special focus on space, by leaving the theatres and occupying supposedly non-artistic spaces, searching for something authentic or wanting to contradict the seemingly authentic. This move into the city (and very often to the outskirts of the city, to empty industrial areas, half ruins of factories, vast storage places…) is closely linked to the desire for the real. This is what lies behind all strands of so-called documentary theatre, which only a few years later became so extremely popular, but it also fits in the logics of gentrification, at least symbolically occupying spaces that were reserved for others.

Using the designated areas of theatre against the grain or even abandoning them not only challenges the institution but the artistic work itself by showing the limitations as well as the possibilities of the genre as such. Working conditions get messy or even tough, chance might take over, audience has to be organised differently, technical possibilities are limited. Site specific work cannot just transfer the logic of a theatre venue into another spatial situation. It needs to be more than a mere reaction to the situation, a pragmatic response that deals with the disadvantages or adapts initial plans just as much as necessary. Site specific work gains momentum when it adapts the logic of the circumstances, pushes them or purposely contradicts them. It needs to be context responsive and make the space as such (and not only a limited portion e.g. in form of a set) part of its form and content – but not by surrendering: Obedience towards the space easily creates boredom – when narration, atmosphere, movement, space etc. come to close to each other, it might result simply in a semantic shortcut – and all artistic tension is gone.

Matthias Lilienthal, X-Apartments

X-Apartments Beirut, 2013 (above left); Nurkan Erpulat, X-Apartments Mannheim, 2011 (above right); and Urban Guerilla Gardening,

X-Apartments Warsaw, 2010 (left).

Photography beirut © Elsie Haddad

Photography mannheim © Florian Merdes

Photography warsaw © Adam Walicki

X-Apartments Beirut, 2013 (above left); Nurkan Erpulat, X-Apartments Mannheim, 2011 (above right); and Urban Guerilla Gardening,

X-Apartments Warsaw, 2010 (left).

Photography beirut © Elsie Haddad

Photography mannheim © Florian Merdes

Photography warsaw © Adam Walicki

Apartments & Stadions

One of the most famous site specific curatorial projects in performing arts, X Apartments by the German dramaturge and founding director of the influential Berlin HAU theatre, Matthias Lilienthal, actually has an even more famous predecessor. For the iconic exhibition Chambres d’Amis (Guest Rooms) in 1986, curator Jan Hoet convinced more than 50 inhabitants of the city of Gent to let artists work in and with their apartments. His concept of “displacement”, which he later also used for documenta 9, aimed for the shifts in perception that happens when something is experienced in an unusual context. He removed the art from the exclusive gallery spaces it usually is bound to: “I am disturbed by the idea that art is here, and reality is there, separated.” In Chambres d’Amis one should “have the impression that you are in the work, not just in front of it.”10 Each artist (among them Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, and Mario Merz) used one or two rooms to create a work that reflected the surrounding environment. Since these were apartments in use, encounters and discussions with the owners were an integral part of the concept.

While Chambres d’Amis exclusively featured works of visual art, it effectively created its own performativity by triggering the imagination of the visitors: the walks between the flats enabled very different individual narrations and dramaturgies, and in the private settings in the apartments were just as open to interpretation as the artworks themselves.

Matthias Lilienthal enhanced this aspect years later with X-Apartments by primarily commissioning theatre directors, choreographers, performers (among them Fatih Akin, Pawel Althamer, andcompany&Co., Herbert Fritsch, Heiner Goebbels, Jonathan Meese, Peaches, raumlaborberlin, Meg Stuart, Anna Viebrock, Barbara Weber, Krysztof Warlikowski etc.) to invent small performances within different apartments.11 By introducing a time structure (the audience stays for the whole time of each short apartment performance and then wanders on while the next group arrives) it collectivises the experience for the visitors. Not only the different “venues” themselves, also the bodies moving from space to space are part of this experience which is more than the sum of the performances. X-Apartments plays with the spirit of an expedition, it connects the audience, which is arbitrarily mixed and might not have known each other before. In the best cases these small scenes, interventions, installations create their own fantasies about the flats, their use, their inhabitants. They extend the “real” settings into the field of imagination or artistically frame documentary approaches. The less successful sequences on the other hand tend to fall into the trap of inherent voyeurism or they rely mainly on fetishizing and exoticising the lives of members of other social groups

or classes.

While the quantity of flats, the extraordinary in the ordinary, the shift of perception towards every day settings are key in X Apartments, Polish curator Joanna Warsza chose a venue with symbolic power for her project Finissage of Stadium X (2006–2008): the 10th Anniversary Stadium in Warsaw that was built in 1955 from the rubble of the war-ruined Polish capital. The stadium represented the idea of Communism and a new Poland. However, by the mid-80s it was abandoned and became a modern ruin itself. New life was infused by Vietnamese and Russian traders who took over as pioneers of the newly arrived capitalism. The stadium thus became the open-air market Jarmark Europa, the only multicultural site in the city; a realm of informality and discount shopping as well as a paradise and work camp for botanists.

The heterogeneity of the site, the usually invisible Vietnamese community, the debates around the new national stadium built for the European soccer championship in 2012 and the lack of a critical debate on Poland’s post-war architectural legacy inspired the three years Finissage of Stadium X. It included an acoustic walk around the Vietnamese sector (A Trip to Asia, 2006), Boniek!, a one man re-enactent of the legendary 1982 Poland-Belgium soccer match by Massimo Furlan (2007), or the Radio Stadion broadcasts by Radio Simulator and backyardradio (2008). Subjective excursions were guided by artists and activists into the stadium that no longer existed. In this project the venue itself was the main protagonist – not only the mere architecture but as well the symbolic role it played for Warsaw (and by this almost being a metaphor for the changes that Poland underwent).

A building as performance

An almost ironic twist to the notion of site specificity brought the project The Theatre by architect Tor Lindstrand and choreographer and theorist Mårten Spångberg. Their long-term interdisciplinary project “International Festival”, created in 2004, positioned itself somewhere between theatre, choreography, architecture and curating. Playfully and sometimes subversively they isolated and investigated different aspects of what a festival consists of: The Welcome Package for example, commissioned by Tanz im August in Berlin 2004, was an “extended bag”, seemingly like the ones many festivals give to invited artists to provide them with information and some presents: “The 18 objects of the package were designed in order to produce a heterogeneous attention to the conventions and economies of festival,”12 for example by giving each participant a different DVD to encourage exchange after watching. Or IF Perfume (2005) for Kaaitheater in Brussels: Small bottles of perfume were given to the audience without further instructions. “During the event, which consisted of works by over 50 choreographers, the fragrance was spread and used by the audience, the use created an intense sense of space, community and intimacy.”13 The idea of curating not only other artists but also performers and even other festivals, was consequently radicalized with IF Plastic Bags, thousands of plastic bags with the IF logo given by International Festival to theatre venues all over Europe for them to use and to distribute – and thus creating an “open script for a potential choreography of 25.000 performers, a kind of inter European dance performed through our everyday movements.”14

For steirischer herbst 2007, International Festival developed their most ambitious project by far. A complete venue was built as a performance and as a curatorial statement: The Theatre originated from the idea that theatre originally was public action in public space (and today is mostly turned into a private action in a private or semi-private room). It was an attempt to revive the old machinery by re-enacting theatre as such by building a theatre. The development of The Theatre was accompanied by a series of workshops involving different artists, architects, theoreticians etc. – itself a kind of social performance with open result. The Theatre turned everything what in theatre is not theatre into theatre – including the 12 x 12 meter flexible stage. As important as this conceptual trick, which enabled a different view on the notion of space by turning it into a performance and by this into a time based art work, was the disinterest in the things that normally would have played an important role as well. The aesthetics of the architecture were rather generic and pragmatic – and the programming of the space mainly delegated to the festivals curators.

Living Exhibitions

Escaping the highly determined and symbolically loaded spaces of theatre might mean ending up in spaces that are even more determined and symbolically loaded: the white cubes of museums and galleries. The increasing interest in all kinds of “living exhibitions” in the last years has many reasons, some as profane as trying to get into other markets or into discourses with seemingly higher prestige. But for most artists and curators the initial motivation is still close to Hoet’s idea of “displacement”. By changing the institutional, aesthetical and architectural frame, the grids of perception and reflection change was well.

Curator Hans Ulrich Obrist has been for many years one of the main protagonists in integrating performative aspects into visual art exhibitions. Already since the 1990s he has collaborated with choreographers like Meg Stuart and Xavier Le Roy,15 and later has produced several time based shows, as Il Tempo del Postino in 2007 (together with Philippe Parreno).16 Tino Sehgal, probably by far the best known contemporary artist inserting live arts into museums and galleries, produces his work always on the line between choreography and visual art. Many of his thoughts on performance are shared by Xavier Le Roy, who collaborated with him e.g. in Project (2003). In 2012 Le Roy showed his live exhibition Retrospective for the fist time. It was “an exhibition conceived as a choreography of actions that will be carried out by performers for the duration of the exhibition.”17 Le Roy uses the format and genre of a retrospectives to re-visit material from his solo choreographies by letting the performers re-create their own memories and stories connected to them. And he emphasises the concept of time by producing frictions between the different time experiences that are brought together: The time span of his revisited oeuvre, the time spent by each visitor, the working time of the performers, and the duration of the whole exhibition which creates with its permanent changes an own dramaturgy. Retrospective “compose(s) situations that inquire into various experiences about how we use, consume or produce time.”18

But while in Retrospective time is a key consideration, for many other live exhibitions it seems to be rather an accessory: As much as Obrist verbally stresses his interest in duration, looking closely at his time based curations, the real potential of liveness seems rather neglected: 11 Rooms19 (co-curated with Klaus Biesenbach) for example is an exhibition placing eleven live art works in eleven white cubes: the performances are clearly framed as works of arts, like objects in a rather old-fashioned exhibition. The performances last the whole day throughout the duration of the exhibition. But the conventions of watching are not challenged. Maybe the time of watching is longer than the infamous average 30 seconds devoted to each art work in most exhibitions, but there is no interest in creating a durational experience of the visitor, not even in the durational experience of the performer, the changing of his body, his attitude etc. It is durational, because that’s what the classic format of exhibition demands. For Obrist and many of the artists he works with, the main interest is to replace objects with people – not to develop art works consisting of people. The approach is (with some exceptions) mostly sculptural or spatial: The material is the human being. Or as Obrist says himself: 11 Rooms is “like a sculpture gallery where all the sculptures go home at 6pm.”20

One of the most famous site specific curatorial projects in performing arts, X Apartments by the German dramaturge and founding director of the influential Berlin HAU theatre, Matthias Lilienthal, actually has an even more famous predecessor. For the iconic exhibition Chambres d’Amis (Guest Rooms) in 1986, curator Jan Hoet convinced more than 50 inhabitants of the city of Gent to let artists work in and with their apartments. His concept of “displacement”, which he later also used for documenta 9, aimed for the shifts in perception that happens when something is experienced in an unusual context. He removed the art from the exclusive gallery spaces it usually is bound to: “I am disturbed by the idea that art is here, and reality is there, separated.” In Chambres d’Amis one should “have the impression that you are in the work, not just in front of it.”10 Each artist (among them Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, and Mario Merz) used one or two rooms to create a work that reflected the surrounding environment. Since these were apartments in use, encounters and discussions with the owners were an integral part of the concept.

While Chambres d’Amis exclusively featured works of visual art, it effectively created its own performativity by triggering the imagination of the visitors: the walks between the flats enabled very different individual narrations and dramaturgies, and in the private settings in the apartments were just as open to interpretation as the artworks themselves.

Matthias Lilienthal enhanced this aspect years later with X-Apartments by primarily commissioning theatre directors, choreographers, performers (among them Fatih Akin, Pawel Althamer, andcompany&Co., Herbert Fritsch, Heiner Goebbels, Jonathan Meese, Peaches, raumlaborberlin, Meg Stuart, Anna Viebrock, Barbara Weber, Krysztof Warlikowski etc.) to invent small performances within different apartments.11 By introducing a time structure (the audience stays for the whole time of each short apartment performance and then wanders on while the next group arrives) it collectivises the experience for the visitors. Not only the different “venues” themselves, also the bodies moving from space to space are part of this experience which is more than the sum of the performances. X-Apartments plays with the spirit of an expedition, it connects the audience, which is arbitrarily mixed and might not have known each other before. In the best cases these small scenes, interventions, installations create their own fantasies about the flats, their use, their inhabitants. They extend the “real” settings into the field of imagination or artistically frame documentary approaches. The less successful sequences on the other hand tend to fall into the trap of inherent voyeurism or they rely mainly on fetishizing and exoticising the lives of members of other social groups

or classes.

While the quantity of flats, the extraordinary in the ordinary, the shift of perception towards every day settings are key in X Apartments, Polish curator Joanna Warsza chose a venue with symbolic power for her project Finissage of Stadium X (2006–2008): the 10th Anniversary Stadium in Warsaw that was built in 1955 from the rubble of the war-ruined Polish capital. The stadium represented the idea of Communism and a new Poland. However, by the mid-80s it was abandoned and became a modern ruin itself. New life was infused by Vietnamese and Russian traders who took over as pioneers of the newly arrived capitalism. The stadium thus became the open-air market Jarmark Europa, the only multicultural site in the city; a realm of informality and discount shopping as well as a paradise and work camp for botanists.

The heterogeneity of the site, the usually invisible Vietnamese community, the debates around the new national stadium built for the European soccer championship in 2012 and the lack of a critical debate on Poland’s post-war architectural legacy inspired the three years Finissage of Stadium X. It included an acoustic walk around the Vietnamese sector (A Trip to Asia, 2006), Boniek!, a one man re-enactent of the legendary 1982 Poland-Belgium soccer match by Massimo Furlan (2007), or the Radio Stadion broadcasts by Radio Simulator and backyardradio (2008). Subjective excursions were guided by artists and activists into the stadium that no longer existed. In this project the venue itself was the main protagonist – not only the mere architecture but as well the symbolic role it played for Warsaw (and by this almost being a metaphor for the changes that Poland underwent).

A building as performance

An almost ironic twist to the notion of site specificity brought the project The Theatre by architect Tor Lindstrand and choreographer and theorist Mårten Spångberg. Their long-term interdisciplinary project “International Festival”, created in 2004, positioned itself somewhere between theatre, choreography, architecture and curating. Playfully and sometimes subversively they isolated and investigated different aspects of what a festival consists of: The Welcome Package for example, commissioned by Tanz im August in Berlin 2004, was an “extended bag”, seemingly like the ones many festivals give to invited artists to provide them with information and some presents: “The 18 objects of the package were designed in order to produce a heterogeneous attention to the conventions and economies of festival,”12 for example by giving each participant a different DVD to encourage exchange after watching. Or IF Perfume (2005) for Kaaitheater in Brussels: Small bottles of perfume were given to the audience without further instructions. “During the event, which consisted of works by over 50 choreographers, the fragrance was spread and used by the audience, the use created an intense sense of space, community and intimacy.”13 The idea of curating not only other artists but also performers and even other festivals, was consequently radicalized with IF Plastic Bags, thousands of plastic bags with the IF logo given by International Festival to theatre venues all over Europe for them to use and to distribute – and thus creating an “open script for a potential choreography of 25.000 performers, a kind of inter European dance performed through our everyday movements.”14

For steirischer herbst 2007, International Festival developed their most ambitious project by far. A complete venue was built as a performance and as a curatorial statement: The Theatre originated from the idea that theatre originally was public action in public space (and today is mostly turned into a private action in a private or semi-private room). It was an attempt to revive the old machinery by re-enacting theatre as such by building a theatre. The development of The Theatre was accompanied by a series of workshops involving different artists, architects, theoreticians etc. – itself a kind of social performance with open result. The Theatre turned everything what in theatre is not theatre into theatre – including the 12 x 12 meter flexible stage. As important as this conceptual trick, which enabled a different view on the notion of space by turning it into a performance and by this into a time based art work, was the disinterest in the things that normally would have played an important role as well. The aesthetics of the architecture were rather generic and pragmatic – and the programming of the space mainly delegated to the festivals curators.

Living Exhibitions

Escaping the highly determined and symbolically loaded spaces of theatre might mean ending up in spaces that are even more determined and symbolically loaded: the white cubes of museums and galleries. The increasing interest in all kinds of “living exhibitions” in the last years has many reasons, some as profane as trying to get into other markets or into discourses with seemingly higher prestige. But for most artists and curators the initial motivation is still close to Hoet’s idea of “displacement”. By changing the institutional, aesthetical and architectural frame, the grids of perception and reflection change was well.

Curator Hans Ulrich Obrist has been for many years one of the main protagonists in integrating performative aspects into visual art exhibitions. Already since the 1990s he has collaborated with choreographers like Meg Stuart and Xavier Le Roy,15 and later has produced several time based shows, as Il Tempo del Postino in 2007 (together with Philippe Parreno).16 Tino Sehgal, probably by far the best known contemporary artist inserting live arts into museums and galleries, produces his work always on the line between choreography and visual art. Many of his thoughts on performance are shared by Xavier Le Roy, who collaborated with him e.g. in Project (2003). In 2012 Le Roy showed his live exhibition Retrospective for the fist time. It was “an exhibition conceived as a choreography of actions that will be carried out by performers for the duration of the exhibition.”17 Le Roy uses the format and genre of a retrospectives to re-visit material from his solo choreographies by letting the performers re-create their own memories and stories connected to them. And he emphasises the concept of time by producing frictions between the different time experiences that are brought together: The time span of his revisited oeuvre, the time spent by each visitor, the working time of the performers, and the duration of the whole exhibition which creates with its permanent changes an own dramaturgy. Retrospective “compose(s) situations that inquire into various experiences about how we use, consume or produce time.”18

But while in Retrospective time is a key consideration, for many other live exhibitions it seems to be rather an accessory: As much as Obrist verbally stresses his interest in duration, looking closely at his time based curations, the real potential of liveness seems rather neglected: 11 Rooms19 (co-curated with Klaus Biesenbach) for example is an exhibition placing eleven live art works in eleven white cubes: the performances are clearly framed as works of arts, like objects in a rather old-fashioned exhibition. The performances last the whole day throughout the duration of the exhibition. But the conventions of watching are not challenged. Maybe the time of watching is longer than the infamous average 30 seconds devoted to each art work in most exhibitions, but there is no interest in creating a durational experience of the visitor, not even in the durational experience of the performer, the changing of his body, his attitude etc. It is durational, because that’s what the classic format of exhibition demands. For Obrist and many of the artists he works with, the main interest is to replace objects with people – not to develop art works consisting of people. The approach is (with some exceptions) mostly sculptural or spatial: The material is the human being. Or as Obrist says himself: 11 Rooms is “like a sculpture gallery where all the sculptures go home at 6pm.”20

Tor Lindstrand and Mårten Spångberg/ International Festival,

The Theatre, steirischer herbst 2007.

Photography: Paul Ott (right), augennerv (left)

The Theatre, steirischer herbst 2007.

Photography: Paul Ott (right), augennerv (left)

Too long, too short, too fast, too slow

But time is a more powerful tool than this. Non-dramatic or post-dramatic theatre for example “instead of employing a fictional Welt-Zeit” (thus pretending a different time-reality) insists “on constituting onstage time and space”. “What’s special about this kind of theatre is the orientation of the whole theatre situation towards the relationship between players and audience.”21 Theatre in this understanding is not necessarily defined through a story, through fiction, through make-believe and dramaturgical arches etc. (even though it can have all this) – it is defined by creating a temporary shared reality. And this is an opportunity also for performative curating.

Truth is concrete22 was an ambitious curatorial project happing in September 2012 in Graz, Austria, in which we (the curatorial team of steirischer herbst festival) attempted to push this notion to an extreme. Starting point was the strong impression by the role of artists in the political turmoil all over the world (from Tahrir to Syntagma, from Zuccotti to Taksim Square, from Japan after Fukushima to Moscow during the wave of demonstrations, from London, Budapest, Athens, Istanbul, to Ramallah, Tel Aviv, Tunis, Rio…) and the open question what role artistic strategies could play in these situations. Perceived well before the Occupy movement began and happening shortly after its first anniversary, the Truth is concrete-marathon camp brought together more than 200 artists, activists, and theorists. They were joined by 100 students and young professionals, as well as by a local and international audience, to meet on the small common ground of art and activism: a 24 hour a day, seven day a week marathon camp with 170 hours of lectures, performances, productions, discussions to pool useful strategies and tactics in art and politics.

The marathon machine ran nonstop – often too fast, sometimes too slow – all day every day and all night every night. It produced thought, arguments, knowledge, but it also created frustration and exhaustion. It used time as a tool to create an extreme social experience. But wasn’t it by doing so just a mirror or even a fulfilment of the neoliberal agenda of more and more, of extreme labour and permanent availability? Did it not just prolong the race we are struggling with in our capitalist environment? Wouldn’t it be better to slow down, to take time?

Truth is concrete aimed in the opposite direction. Taking a break was not going to help. This machine did not set a task that could be fulfilled. It could not be easily commodified, nor easily consumed. There was no right time; it wasn’t built around highlights. There was no ideal amount of hours to grasp it the right way. So there was actually not one marathon, but many individual ones: some shorter, some longer; some searching for depth in familiar topics, others searching for things one had no idea about yet. Having to miss out was part of having to make choices.

In this way, it was also a metaphor for political movements: spending an hour or so at Occupy Wall Street, you will talk to some people, see some tents,

possibly smell some of the spirit. You come back, listen in to some committee meetings, maybe next time start talking yourself. Or you move in. All is possible, but it will give you different intensities and insights. Truth is concrete was not only interested in the intellectual intensity it produced. It was also interested in physical intensity. In the impact this meeting had on our bodies. In the here and now.

It was as machinic, as rigid, marathon running in the centre, surrounded by a camplike living and working environment developed by raumlaborberlin – a social space with its own needs and timings, creating a one week community, mixing day and night, developing its own jetlag toward the outside world. The vertical gesture of the marathon machine was embedded in a horizontal structure of openness: with organized one day workshops and several durational projects and an exhibition, but most importantly with the parallel “Open marathon” based on self-organization: its contents were produced entirely by participants spontaneously stepping into the slots.23

But time is a more powerful tool than this. Non-dramatic or post-dramatic theatre for example “instead of employing a fictional Welt-Zeit” (thus pretending a different time-reality) insists “on constituting onstage time and space”. “What’s special about this kind of theatre is the orientation of the whole theatre situation towards the relationship between players and audience.”21 Theatre in this understanding is not necessarily defined through a story, through fiction, through make-believe and dramaturgical arches etc. (even though it can have all this) – it is defined by creating a temporary shared reality. And this is an opportunity also for performative curating.

Truth is concrete22 was an ambitious curatorial project happing in September 2012 in Graz, Austria, in which we (the curatorial team of steirischer herbst festival) attempted to push this notion to an extreme. Starting point was the strong impression by the role of artists in the political turmoil all over the world (from Tahrir to Syntagma, from Zuccotti to Taksim Square, from Japan after Fukushima to Moscow during the wave of demonstrations, from London, Budapest, Athens, Istanbul, to Ramallah, Tel Aviv, Tunis, Rio…) and the open question what role artistic strategies could play in these situations. Perceived well before the Occupy movement began and happening shortly after its first anniversary, the Truth is concrete-marathon camp brought together more than 200 artists, activists, and theorists. They were joined by 100 students and young professionals, as well as by a local and international audience, to meet on the small common ground of art and activism: a 24 hour a day, seven day a week marathon camp with 170 hours of lectures, performances, productions, discussions to pool useful strategies and tactics in art and politics.

The marathon machine ran nonstop – often too fast, sometimes too slow – all day every day and all night every night. It produced thought, arguments, knowledge, but it also created frustration and exhaustion. It used time as a tool to create an extreme social experience. But wasn’t it by doing so just a mirror or even a fulfilment of the neoliberal agenda of more and more, of extreme labour and permanent availability? Did it not just prolong the race we are struggling with in our capitalist environment? Wouldn’t it be better to slow down, to take time?

Truth is concrete aimed in the opposite direction. Taking a break was not going to help. This machine did not set a task that could be fulfilled. It could not be easily commodified, nor easily consumed. There was no right time; it wasn’t built around highlights. There was no ideal amount of hours to grasp it the right way. So there was actually not one marathon, but many individual ones: some shorter, some longer; some searching for depth in familiar topics, others searching for things one had no idea about yet. Having to miss out was part of having to make choices.

In this way, it was also a metaphor for political movements: spending an hour or so at Occupy Wall Street, you will talk to some people, see some tents,

possibly smell some of the spirit. You come back, listen in to some committee meetings, maybe next time start talking yourself. Or you move in. All is possible, but it will give you different intensities and insights. Truth is concrete was not only interested in the intellectual intensity it produced. It was also interested in physical intensity. In the impact this meeting had on our bodies. In the here and now.

It was as machinic, as rigid, marathon running in the centre, surrounded by a camplike living and working environment developed by raumlaborberlin – a social space with its own needs and timings, creating a one week community, mixing day and night, developing its own jetlag toward the outside world. The vertical gesture of the marathon machine was embedded in a horizontal structure of openness: with organized one day workshops and several durational projects and an exhibition, but most importantly with the parallel “Open marathon” based on self-organization: its contents were produced entirely by participants spontaneously stepping into the slots.23

Truth is concrete.

A 24/7 marathon camp on artistic strategies in politics,

steirischer herbst 2012.

Photography:

Wolfgang Silveri

Thomas Raggam

Performing Knowledge

If performative curating understands itself as creating framed social situations in space and time, then production and exchange of knowledge are key issues – and can be found in many of the already mentioned projects as a main purpose.

Also Boris Charmatz’ expo zéro (since 2009) falls in this category: As part of his Musée de la danse it is created as an exhibition, a living, a dancing, a talking exhibition – and a permanent exchange. Experts from different fields – choreographers, writers, performers, directors, theorists, visual artists, architects – first spend four days in a kind of think tank together and then open the space to the public, present movements, thoughts, words… and engage with each other in verbal and non-verbal communications. What belongs in a Musée de la danse? Thinking the museum means at the same time creating it – a museum of dance can only be ephemeric (the “zero” in the title refers to the lack of objects).

Matthias von Hartz’ “go create™ resistance” (2002–2005) was not a museum but a different kind of public space. He developed a series of evenings focussing on art and activism at Schauspielhaus Hamburg, one of the strongholds of Bourgeois’ culture. Or the “Dictionary of War” (2006/2007),24 a collaborative platform for creating 100 concepts on the subject of war. During four two-day events in Frankfurt, Munich, Graz and Berlin scientists, artists, theorists and practitioners presented their entries to the dictionary as lectures, performances, films, slide shows, readings, concerts in strict alphabetical order as a marathon discourse. From ABC weapons to civilian population, from parachute invasion to facts on the ground, potato to collateral damage, info war to radar surveillance, and homesickness to resistance. All entries were filmed and uploaded to a video dictionary that later on was enlarged by further contributions inother cities.25

Maybe best known on the field of artistic and curatorial knowledge projects are the installations for knowledge distribution by Hannah Hurtzig: In her work theory and praxis, content and form are hardly dividable anymore. The Kiosk for Useful Knowledge for example – a format she originally devised together with curator Anselm Francke – is a “construction of public spaces experimenting with new narrative formats for the production and mediation of knowledge.”26 Professional knowledge and theoretical discourses meet individual narrations; the distribution of knowledge becomes graspable for an audience that is voyeur and witness at the same time of a almost intimate conversation: Two protagonists exchange their expertise in form of a personal narration, which we can only participate in in a mediated way by transmitted image and sound. A principle which is multiplied in the Blackmarket for Useful Knowldege and Non-Knowledge, an installation for 50 to 100 experts on small tables. Here, everyone can buy half an hour of intimate expert knowledge for one Euro from scientists, artists, hair dressers, fortune tellers: facts, experiences, self-help or simply insights into areas of knowledge completely unknown to you – knowledge that is always connected to the person who is passing it on. And to the way how it is passed on. In all her knowledge installations, Hannah Hurtzig emphasises the perfomative character of knowledge exchange.27

If performative curating understands itself as creating framed social situations in space and time, then production and exchange of knowledge are key issues – and can be found in many of the already mentioned projects as a main purpose.

Also Boris Charmatz’ expo zéro (since 2009) falls in this category: As part of his Musée de la danse it is created as an exhibition, a living, a dancing, a talking exhibition – and a permanent exchange. Experts from different fields – choreographers, writers, performers, directors, theorists, visual artists, architects – first spend four days in a kind of think tank together and then open the space to the public, present movements, thoughts, words… and engage with each other in verbal and non-verbal communications. What belongs in a Musée de la danse? Thinking the museum means at the same time creating it – a museum of dance can only be ephemeric (the “zero” in the title refers to the lack of objects).

Matthias von Hartz’ “go create™ resistance” (2002–2005) was not a museum but a different kind of public space. He developed a series of evenings focussing on art and activism at Schauspielhaus Hamburg, one of the strongholds of Bourgeois’ culture. Or the “Dictionary of War” (2006/2007),24 a collaborative platform for creating 100 concepts on the subject of war. During four two-day events in Frankfurt, Munich, Graz and Berlin scientists, artists, theorists and practitioners presented their entries to the dictionary as lectures, performances, films, slide shows, readings, concerts in strict alphabetical order as a marathon discourse. From ABC weapons to civilian population, from parachute invasion to facts on the ground, potato to collateral damage, info war to radar surveillance, and homesickness to resistance. All entries were filmed and uploaded to a video dictionary that later on was enlarged by further contributions inother cities.25

Maybe best known on the field of artistic and curatorial knowledge projects are the installations for knowledge distribution by Hannah Hurtzig: In her work theory and praxis, content and form are hardly dividable anymore. The Kiosk for Useful Knowledge for example – a format she originally devised together with curator Anselm Francke – is a “construction of public spaces experimenting with new narrative formats for the production and mediation of knowledge.”26 Professional knowledge and theoretical discourses meet individual narrations; the distribution of knowledge becomes graspable for an audience that is voyeur and witness at the same time of a almost intimate conversation: Two protagonists exchange their expertise in form of a personal narration, which we can only participate in in a mediated way by transmitted image and sound. A principle which is multiplied in the Blackmarket for Useful Knowldege and Non-Knowledge, an installation for 50 to 100 experts on small tables. Here, everyone can buy half an hour of intimate expert knowledge for one Euro from scientists, artists, hair dressers, fortune tellers: facts, experiences, self-help or simply insights into areas of knowledge completely unknown to you – knowledge that is always connected to the person who is passing it on. And to the way how it is passed on. In all her knowledge installations, Hannah Hurtzig emphasises the perfomative character of knowledge exchange.27

Hannah Hurtzig, Black Market for Useful Knowledge and Non-Knowledge No. 8: The Gift and Other Violations of the Principle of Exchange.

An installation with 100 experts, steirischer herbst 2007.

Photography: Johannes Gellner

An installation with 100 experts, steirischer herbst 2007.

Photography: Johannes Gellner

No fear of the task

All these examples put forward a rather strong emphasis on the curatorial concept. To a large extend they define the artistic works they include, they chose, adapt, produce – and in some cases they even are artistic works themselves (as in the examples of deufert&plischke, Boris Charmatz, International Theater, Hannah Hurtzig etc.). Curatorial thinking starts much earlier though and can play a crucial role also in programming more conventional festival or venue formats.

So what can one see if one attends, on one evening, two clearly juxtaposed performances? How does it change one work retrospectively and the other in advance? (At least an exhibition curator rarely has the possibility of steering the order of reception so precisely.) What influence does it exert on the reception if a leitmotif or a theme is offered as the focus? What reference points can be given for an artwork, perhaps also historically, at least on paper or video? What contexts of experience are created for the spectators already by the very choice of space, the point of time, the graphic design, the advertising strategies? Is it possible not only to scatter theoretical postulates like parsley over the programme, but also actually mix them in?

This list can be continued, it gives only some arbitrary examples of how contexts and focuses can be created, if so through the elaboration of smaller sections or agglomerations/knots in the programme as a whole. After all, biennials and museums are usually no adroit ships as well – and yet they play increasingly often with their temporal axis, with the idea of the performative, the social. So the attention towards an arch, towards constructive frictions or additions, towards a dramaturgy of programming is also an attempt at recovering lost terrain for theatre as a form of art. A course of events, a change of tempo, a change of intensity, a change of viewpoint. Even if barely any spectator can follow such dramaturgies in their entirety, they are nevertheless perceptible. One can walk through a festival as through a landscape. Some things are accidental, others are obvious. To linger or to go on, to grasp things intuitively or turn them over intellectually. The phantom of the über-curator, boldly creating his own piece out of other people’s artworks, is not to be feared in the performative domain anyway. On the contrary, there is rather a lack of courage for imparting meaning at all – and not least because of modesty, but out of being afraid of the task.

![]()

PDF av artikkel

All these examples put forward a rather strong emphasis on the curatorial concept. To a large extend they define the artistic works they include, they chose, adapt, produce – and in some cases they even are artistic works themselves (as in the examples of deufert&plischke, Boris Charmatz, International Theater, Hannah Hurtzig etc.). Curatorial thinking starts much earlier though and can play a crucial role also in programming more conventional festival or venue formats.

So what can one see if one attends, on one evening, two clearly juxtaposed performances? How does it change one work retrospectively and the other in advance? (At least an exhibition curator rarely has the possibility of steering the order of reception so precisely.) What influence does it exert on the reception if a leitmotif or a theme is offered as the focus? What reference points can be given for an artwork, perhaps also historically, at least on paper or video? What contexts of experience are created for the spectators already by the very choice of space, the point of time, the graphic design, the advertising strategies? Is it possible not only to scatter theoretical postulates like parsley over the programme, but also actually mix them in?

This list can be continued, it gives only some arbitrary examples of how contexts and focuses can be created, if so through the elaboration of smaller sections or agglomerations/knots in the programme as a whole. After all, biennials and museums are usually no adroit ships as well – and yet they play increasingly often with their temporal axis, with the idea of the performative, the social. So the attention towards an arch, towards constructive frictions or additions, towards a dramaturgy of programming is also an attempt at recovering lost terrain for theatre as a form of art. A course of events, a change of tempo, a change of intensity, a change of viewpoint. Even if barely any spectator can follow such dramaturgies in their entirety, they are nevertheless perceptible. One can walk through a festival as through a landscape. Some things are accidental, others are obvious. To linger or to go on, to grasp things intuitively or turn them over intellectually. The phantom of the über-curator, boldly creating his own piece out of other people’s artworks, is not to be feared in the performative domain anyway. On the contrary, there is rather a lack of courage for imparting meaning at all – and not least because of modesty, but out of being afraid of the task.

PDF av artikkel

Notes

1B-Visible, curated by the choreographers Kattrin Deufert and Thomas Plischke together with the dramaturge Jeroen Peeters, took place at Kunstencentrum Vooruit, Gent/Belgium in in November 2002.

2 Art critic Nicolas Bourriaud coined the term “relational aesthetics” for this in the late 1990s.

3 Hans Ulrich Obrist “Diaghilev is the most important curator of the 20th century”. In: Florian Malzacher, Tea Tupajića and Petra Zanki (Eds.). Curating Performing Arts. Zagreb: Frakcija Performing Arts Journal: 2010, p. 44.

4 For a more extensive reflection on the different conditions of curating in visual and in performing arts, as well as criteria, relation towards the market etc. see also: Florian Malzacher “Cause & Result. About a job with an unclear profile, aim and future”. In: Florian Malzacher, Tea Tupajić and Petra Zanki (Eds.). Curating Performing Arts. Zagreb: Frakcija Performing Arts Journal: 2010, p. 10–19.

5 Claire Bishop. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics

of Spectatorship. London and New York: Verso, 2012, p. 2.

6 Beatrice von Bismarck and Irit Rogoff. “A conversation between Irit Rogoff and Beatrice von Bismarck”. In: Beatrice v. Bismarck, Jörn Schafaff, Thomas Weski (Eds.). Cultures of the Curatorial. Sternberg Press: Berlin, 2012, p. 24–25.

7 Beatrice von Bismarck and Irit Rogoff. “A conversation

between Irit Rogoff and Beatrice von Bismarck”. In: Beatrice v. Bismarck, Jörn Schafaff, Thomas Weski (Eds.). Cultures of the Curatorial. Sternberg Press: Berlin, 2012, p. 23.

8 Heiner Müller in conversation with Alexander Kluge:

http://muller-kluge.library.cornell.edu/en/video_transcript.php?f=121

9 Hannah Arendt. The Human Condition. University of

Chicago Press, 1989, p. 188.

10 “Avant-Garde Art Show Adorns Belgian Homes”. The New York Times. August 19th, 1986.

11 Initially invented for the festival Theater der Welt 2002 in Duisburg, the format proved to be so successful and adaptable that since then new versions took place in cities such as Berlin, Caracas, Warsaw, Vienna, São Paulo, Johannesburg or Istanbul, often with different co-curators and collaborators.

12 http://international-festival.org/node/3

13 http://international-festival.org/node/4

14 http://international-festival.org/node/56

15 E.g. In Laboratorium (curated together with Barbara Vanderlinden), Antwerp 1999.

16 A timebased group show with Liam Gillick, Tino Seghal,

Tacita Dean, Carsten Höller, Olafur Eliasson, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster and others.

17 http://www.xavierleroy.com/page.php?sp=2d6b21a02b428a09f2ebd3d6cbaf2f6be1e3848d&lg=en

18 http://www.xavierleroy.com/page.php?sp=2d6b21a02b428a09f2ebd3d6cbaf2f6be1e3848d&lg=en

19 The project was shown as 11 Rooms at Manchester International Festival in July 2011 with works by Marina Abramović,

John Baldessari,

Allora and Calzadilla,

Simon Fujiwara,

Joan Jonas,

Laura Lima,

Roman Ondák,

Lucy Raven,

Tino Sehgal,

Santiago Sierra,

Xu Zhen. Later editions took place in Ruhrtriennale, Essen/German (12 Rooms, 2012), Public Art Projects, Sydney/Australia (13 Rooms, 2013), Art Basel, Basel/Switzerland (14 Rooms, 2014). For each edition, the artists list partially changed.

20 http://www.mif.co.uk/event/11-rooms

21 Hans-Thies Lehmann. “Shakespeare’s Grin. Remarks on World Theatre with Forced Entertainment”. Not Even A Game Anymore. The Theatre of Forced Entertainment. Ed./Hg. Judith Helmer and Florian Malzacher. Berlin: Alexander Verlag, 2004, p. 114.

22Truth is concrete. A 24/7 marathon camp on artistic strategies in politics and political strategies in art. steirischer herbst, Graz/Austria 21st–28th September 2012. Curated by Anne Faucheret, Veronica Kaup-Hasler, Kira Kirsch and Florian Malzacher (idea and concept).

23 There are obviously many other good examples for using time as a curatorial means: E.g. Matthias Lilienthal’s Unendlicher Spaß (Berlin, 2012 after David Foster Wallace’s novel Infinite Jest) stressed duration as well as site speficity: The audience followed for twentyfour hours from one scene to the other, partly by foot (mainly within the premises of a large Sport areal), partly by bus throughout the patina of the old west of Berlin.

The opposite approach – shortening the length of the performances to a minimum – was used in Tom Stromberg’s project for documenta x (1997): Theaterskizzen (Theatre Sketches) reduced the time for each presentation to a few minutes and thus reduced the possibilities of conventional dramaturgies; a task that almost only Stefan Pucher and Gob Squad with 15 Minutes to comply managed to use convincingly. Even shorter are the slots that the New York based organisation Creative Time – devoted to art in public space – offers at their annual summits: Just eight minutes each artist, theorist, activists.

24Dictionary of War was curated by the curators’ collective Unfriendly Takeover together with the activist collective Multitude e.V. www.dictionaryofwar.org

25 Other projects devoted to the idea of knowledge production and exchange were for example the different conferences and workshops conceived for steirischer herbst’s Spielfeldforschung (Playing field research) between 2006 and 2010 where theory confronted itself with different formats of art. New formats were developed that brought together theory and artistic practise on eyelevel and in proximity, for example the Walks in Progress (2006) that moved through the city as well as through the festival programme. This concept was later developed further into Walking Conferences (2007 and 2008 – curated by Florian Malzacher and Gesa Ziemer). Or the fourth and fifth International Summer Academy at Künstlerhaus Mousonturm in Frankfurt/Main – curated by Thomas Frank (2004), Florian Malzacher (2002 and 2004) Christine Peters (2002), Mårten Spångberg (2002 and 2004) – invited the workshop hosts as well as all contributors to confront themselves with guests that they did not work together yet, or even better: that they always wanted to get to know. And to hand over to them part of the programme. With this concept – inspired by Hans Ulrich Obrist’s concept of “invite to invite” – they put themselves at least in regard of this uncertainty on the same level as other contributors. As well as the curators: Since the invitation was delegated to somebody invited and so the own influence was reduced.

26 http://www.kiosk-berlin.de

27 See also: Florian Malzacher and Gesa Ziemer.

“Das Lachen der anderen. Doing Theory”.

In: Herbst. Theorie zur Praxis (1) 2006.

2 Art critic Nicolas Bourriaud coined the term “relational aesthetics” for this in the late 1990s.

3 Hans Ulrich Obrist “Diaghilev is the most important curator of the 20th century”. In: Florian Malzacher, Tea Tupajića and Petra Zanki (Eds.). Curating Performing Arts. Zagreb: Frakcija Performing Arts Journal: 2010, p. 44.

4 For a more extensive reflection on the different conditions of curating in visual and in performing arts, as well as criteria, relation towards the market etc. see also: Florian Malzacher “Cause & Result. About a job with an unclear profile, aim and future”. In: Florian Malzacher, Tea Tupajić and Petra Zanki (Eds.). Curating Performing Arts. Zagreb: Frakcija Performing Arts Journal: 2010, p. 10–19.

5 Claire Bishop. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics

of Spectatorship. London and New York: Verso, 2012, p. 2.

6 Beatrice von Bismarck and Irit Rogoff. “A conversation between Irit Rogoff and Beatrice von Bismarck”. In: Beatrice v. Bismarck, Jörn Schafaff, Thomas Weski (Eds.). Cultures of the Curatorial. Sternberg Press: Berlin, 2012, p. 24–25.

7 Beatrice von Bismarck and Irit Rogoff. “A conversation

between Irit Rogoff and Beatrice von Bismarck”. In: Beatrice v. Bismarck, Jörn Schafaff, Thomas Weski (Eds.). Cultures of the Curatorial. Sternberg Press: Berlin, 2012, p. 23.

8 Heiner Müller in conversation with Alexander Kluge:

http://muller-kluge.library.cornell.edu/en/video_transcript.php?f=121

9 Hannah Arendt. The Human Condition. University of

Chicago Press, 1989, p. 188.

10 “Avant-Garde Art Show Adorns Belgian Homes”. The New York Times. August 19th, 1986.

11 Initially invented for the festival Theater der Welt 2002 in Duisburg, the format proved to be so successful and adaptable that since then new versions took place in cities such as Berlin, Caracas, Warsaw, Vienna, São Paulo, Johannesburg or Istanbul, often with different co-curators and collaborators.

12 http://international-festival.org/node/3

13 http://international-festival.org/node/4

14 http://international-festival.org/node/56

15 E.g. In Laboratorium (curated together with Barbara Vanderlinden), Antwerp 1999.

16 A timebased group show with Liam Gillick, Tino Seghal,

Tacita Dean, Carsten Höller, Olafur Eliasson, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster and others.

17 http://www.xavierleroy.com/page.php?sp=2d6b21a02b428a09f2ebd3d6cbaf2f6be1e3848d&lg=en

18 http://www.xavierleroy.com/page.php?sp=2d6b21a02b428a09f2ebd3d6cbaf2f6be1e3848d&lg=en

19 The project was shown as 11 Rooms at Manchester International Festival in July 2011 with works by Marina Abramović,

John Baldessari,

Allora and Calzadilla,

Simon Fujiwara,

Joan Jonas,

Laura Lima,

Roman Ondák,

Lucy Raven,

Tino Sehgal,

Santiago Sierra,

Xu Zhen. Later editions took place in Ruhrtriennale, Essen/German (12 Rooms, 2012), Public Art Projects, Sydney/Australia (13 Rooms, 2013), Art Basel, Basel/Switzerland (14 Rooms, 2014). For each edition, the artists list partially changed.

20 http://www.mif.co.uk/event/11-rooms

21 Hans-Thies Lehmann. “Shakespeare’s Grin. Remarks on World Theatre with Forced Entertainment”. Not Even A Game Anymore. The Theatre of Forced Entertainment. Ed./Hg. Judith Helmer and Florian Malzacher. Berlin: Alexander Verlag, 2004, p. 114.

22Truth is concrete. A 24/7 marathon camp on artistic strategies in politics and political strategies in art. steirischer herbst, Graz/Austria 21st–28th September 2012. Curated by Anne Faucheret, Veronica Kaup-Hasler, Kira Kirsch and Florian Malzacher (idea and concept).

23 There are obviously many other good examples for using time as a curatorial means: E.g. Matthias Lilienthal’s Unendlicher Spaß (Berlin, 2012 after David Foster Wallace’s novel Infinite Jest) stressed duration as well as site speficity: The audience followed for twentyfour hours from one scene to the other, partly by foot (mainly within the premises of a large Sport areal), partly by bus throughout the patina of the old west of Berlin.

The opposite approach – shortening the length of the performances to a minimum – was used in Tom Stromberg’s project for documenta x (1997): Theaterskizzen (Theatre Sketches) reduced the time for each presentation to a few minutes and thus reduced the possibilities of conventional dramaturgies; a task that almost only Stefan Pucher and Gob Squad with 15 Minutes to comply managed to use convincingly. Even shorter are the slots that the New York based organisation Creative Time – devoted to art in public space – offers at their annual summits: Just eight minutes each artist, theorist, activists.

24Dictionary of War was curated by the curators’ collective Unfriendly Takeover together with the activist collective Multitude e.V. www.dictionaryofwar.org

25 Other projects devoted to the idea of knowledge production and exchange were for example the different conferences and workshops conceived for steirischer herbst’s Spielfeldforschung (Playing field research) between 2006 and 2010 where theory confronted itself with different formats of art. New formats were developed that brought together theory and artistic practise on eyelevel and in proximity, for example the Walks in Progress (2006) that moved through the city as well as through the festival programme. This concept was later developed further into Walking Conferences (2007 and 2008 – curated by Florian Malzacher and Gesa Ziemer). Or the fourth and fifth International Summer Academy at Künstlerhaus Mousonturm in Frankfurt/Main – curated by Thomas Frank (2004), Florian Malzacher (2002 and 2004) Christine Peters (2002), Mårten Spångberg (2002 and 2004) – invited the workshop hosts as well as all contributors to confront themselves with guests that they did not work together yet, or even better: that they always wanted to get to know. And to hand over to them part of the programme. With this concept – inspired by Hans Ulrich Obrist’s concept of “invite to invite” – they put themselves at least in regard of this uncertainty on the same level as other contributors. As well as the curators: Since the invitation was delegated to somebody invited and so the own influence was reduced.

26 http://www.kiosk-berlin.de

27 See also: Florian Malzacher and Gesa Ziemer.

“Das Lachen der anderen. Doing Theory”.

In: Herbst. Theorie zur Praxis (1) 2006.

Literature

Arendt, Hannah. 1989. The Human Condition.

University of Chicago Press.

“Avant-Garde Art Show Adorns Belgian Homes”. The New York Times. August 19th, 1986.

Bishop, Claire. 2012. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London and New York: Verso.

Bismarck, Beatrice von and Irit Rogoff. “A conversation between Irit Rogoff and Beatrice von Bismarck”. In: Beatrice v. Bismarck, Jörn Schafaff, Thomas Weski (Eds.). 2012. Cultures of the Curatorial. Berlin: Sternberg Press.